SHANGHAI — New York commuters suffer regular delays. Aging tracks at Penn Station are being rebuilt after a series of derailments. The entire subway system is operating under a state of emergency.

Halfway around the world, China is rushing to build new subway systems. Here in Shanghai, three new lines are being extended this year. Trains are nearly always on time.

Chinese officials are quick to say that New York has a model public transport network, albeit one they aspire to emulate more closely in some respects than others.

While the New York system is aging, it still shows the soaring ambition of its original creators in its bold design — express tunnels and stations bring together up to a dozen lines. Shanghai’s is clean, efficient and constantly expanding. But its development also reflects a preoccupation with managing vast crowds and avoiding stampedes, which results in a layout that can make trips longer.

On Time, or All The Time?

Fares on Shanghai’s subway are 3 to 4 renminbi, or 45 to 60 cents, for all but the longest journeys. To the extent that wages in the Chinese city are about a sixth that of New York, they roughly compare to the $2.75 fares in New York.

But the similarities largely end there.

New York’s subway struggles with chronic delays, partly because of mechanical breakdowns but also because of debris on the tracks and even people falling off platforms. The city has begun an intensive campaign of cleaning tracks of debris, to reduce the frequency of fires. Only two lines — the Lexington Avenue subway and the Queens Boulevard line — are able to offer trains every two minutes, and other lines can be much slower. Much of New York’s signal and switch equipment was installed before World War II.

By contrast, Shanghai’s trains are not only frequent but also dependable. The city’s subway claims to have an on-time rate of 99.8 percent. People or trash seldom fall on the tracks: thick, clear barriers of reinforced glass separate the platforms from the tracks, with sliding doors that open only when a train is in the station. Trains run every two minutes on the busiest lines, and almost as frequently on the other lines.

New York does have its advantages — particularly for night owls.

Subway systems in Shanghai, and across China, shut down every evening. Only in the last few months has Shanghai even extended the closing time for its most heavily used lines to midnight, while other routes still close as early as 10:30 p.m.

The Metropolitan Transportation Authority takes pride in keeping all 472 of its stations open 24 hours a day.

It is able to do so because of the foresight of its builders more than a century ago, said Shao Weizhong, the Shanghai Metro vice president overseeing the system’s operations and management centre. The New York system was built with express train tunnels in addition to local train tunnels. So subway cars can take turns during the night running through the local tunnels and the express tunnels, with maintenance conducted on whichever tunnel is not in use.

Shanghai’s subway system, like most such networks around the world, does not have separate local and express tunnels, so the entire system has to stop every night for maintenance. But the system’s newest and most technologically advanced line, Line 14, which is scheduled to open in 2020, will have parallel tracks along at least part of it for ease of maintenance, Mr. Shao said. He added that no decision had been made yet on whether to extend its hours of service.

Workers and Machines

What really separates the Shanghai subway, and those of other Chinese cities, from many Western counterparts, is the speed of construction.

The Metropolitan Transportation Authority has used six giant tunnel-boring machines in recent years across the subway network. Shanghai has 60 such devices working on just one of the many new lines it is building or extending.

“Our working progress is faster than in Western countries — maybe we only take one or two years to finish” a task, said Zhou Xisheng, a 49-year-old deputy chief engineer for Shanghai Metro. “However, in foreign countries, it may take five to ten years.”

Shanghai does not just have more equipment, it also has cheaper labor. Heavy equipment operators earn about $1,000 a month here, a small fraction of what comparable workers earn in New York.

The overall effect is striking: China has completed more miles of subways than the rest of the world in each of the last two years, according to the Brussels-based International Association of Public Transport.

To be fair, a simple count of tunnel-boring machines and labourers is not enough to compare the challenges each city faces in building subway lines.

For starters, not all of New York’s subway construction even uses tunnel-boring machines: Some of it is done by cutting a very deep trench in the ground, laying the new line and then covering it.

A bigger difference is that New York has to cut through solid rock to make new tunnels, while Shanghai is digging through relatively soft, solidified mud left by rivers winding across the Yangtze River delta for millions of years. (But that mud creates another hazard that is less of a worry in New York’s firm bedrock: making sure that the roofs of Shanghai’s subway tunnels do not sag or leak water.)

Squares and Diagonals

Shanghai’s subway may carry nearly twice as many people as New York’s, even though it has a quarter fewer stations. But on a day-to-day basis, the biggest difference between the two networks lies in the complexity of each city’s stations.

The sprawling Times Square station, for example, and its 42nd Street extension have 12 lines, although a few of them share tracks. Across New York’s subway map, no line is rigidly straight throughout.

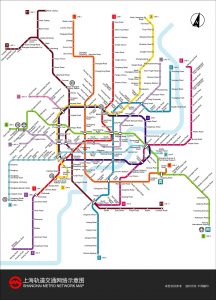

Shanghai, on the other hand, has a subway map that looks more like a rectangular grid — lines run north to south, and east to west, with few exceptions. As a result, most transfer stations involve just two lines, a few have three lines and only one station in the entire network has four.

The lack of “diagonal” lines means that journeys tend to be slightly longer and often involve a transfer — riders in effect go around a square to reach a destination, and have to change trains at the corners.

Line 14, the newest addition to Shanghai’s network, is a notable exception. It will run diagonally along part of its route when it finally opens.

But faced with a city with three times the population of New York, and fearful of overcrowding, Shanghai subway officials say that they prefer the simplicity.

“We try to avoid four-line hubs,” said Li Yingfeng, the chief of the Shanghai subway’s operation management centre, “because we have a much higher ridership than the New York City system.”

With reports from NYT