… seeks new roads to open markets

For years, Uber’s biggest investors dreamt of a winner-takes-all future as they pumped cash into the heavily lossmaking US ride-hailing company.

By undercutting rivals, they imagined a time when the natural network effects of a dominant online marketplace would kick in for Uber, driving out rivals and bringing long-awaited profits.

The global market consolidation is now well underway — but it has been the US company, not its rivals, that has been retrenching. As a result, an industry that has seen the most cut-throat business practices in the past is quickly turning into a tightly linked global oligopoly.

In the latest sign of this ride-hailing shakeout, Uber at the start of this week agreed to fold its business in south-east Asia into local rival Grab. In return, it will get 27.5 percent in the enlarged business — roughly matching its estimated market share in the region — along with a board seat.

The deal ends the rivalry between market-leading Grab and its nearest challenger across a region that includes Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, the Philippines and Myanmar.

It also replicates previous deals in which the US ride-hailing group has withdrawn from China, in return for a 20 percent stake in market leader Didi Chuxing, and in Russia, where it folded into Yandex for a 37 percent in an enlarged market leader.

Uber has at least been able to count its five-year venture into south-east Asia as a financial success, despite its failure to win the battle for market share. In return for a $700m investment in its business in the region, Uber claimed to have received a stake in Grab worth “several billion dollars”.

Share this graphic The deal has valued Uber’s stake in Grab at more than $2bn, putting the value of the entire company at more than $7bn, according to one person familiar with the terms. That compares with the $6bn Grab was valued at when it raised money last year.

Behind the oligopoly that has been forming around ride-hailing is SoftBank, the Japanese investment group, which now owns significant stakes in most of the industry’s leaders. The group has made no secret of its desire to see a more orderly market after an era of expansion that has seen the largest players raise — and spend — huge amounts. SoftBank was Grab’s biggest investor before the Uber deal.

It also poured $9.3bn into Uber in December and has been instrumental in nudging the US company into curtailing lossmaking ventures and focus on markets where it either is — or has the chance to be — the market leader.

In an interview with the Financial Times soon after the investment, Rajeev Misra, head of Softbank’s Vision fund and now a member of Uber’s board said he was urging the ride-hailing group to focus on the US and its key markets rather than on spreading itself across the globe.

The latest deal takes Masayoshi Son, SoftBank’s founder, one step further in his ambitions of having key stakes in ride-hailing groups worldwide. In securing a substantial discount to its stake in Uber, one of SoftBank’s arguments was that it was invested in and could therefore influence Uber’s competitors across Asia, according to two investors with direct knowledge of the matter.

But not all are happy. Much of the red ink that has flowed in the ride-hailing business has resulted from price competition, as the companies used subsidies to lure riders. If peace has broken out in some of the largest ride-hailing markets, critics say that could lead to higher prices and less choice for consumers.

Among them is Here, the digital-mapping company that is majority-owned by a consortium of German carmakers. They could be among the most affected by consolidation, since the ride-hailing market is likely to become an increasingly significant target for car companies.

“The mobility space is getting very consolidated — we have a few giants globally,” said Liad Itzhak, vice-president of Here Mobility, which has built its own platform to support smaller ride-hailing services. Mr Itzhak added that “they are signing agreements to leave a big player as a monopoly” in each market.

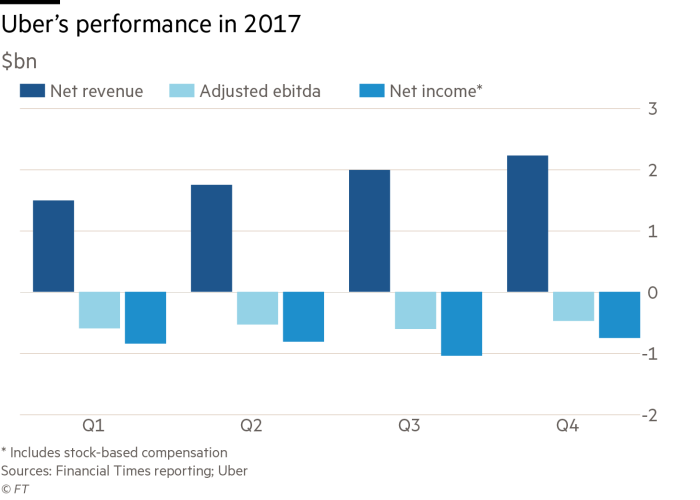

For San Francisco-based Uber, the retrenchment marks another step towards a hoped-for stock market listing next year. It has been bleeding cash, and suffered a string of scandals last year that led to the exit of former boss Travis Kalanick. However, under new chief executive Dara Khosrowshahi, the company has tightened financial discipline and narrowed adjusted losses to $741m in the fourth quarter, from $1bn in the previous three months.

The question now is whether further cuts will be needed. Mr Khosrowshahi sought to draw a line under his company’s retreat this week, using a blog post to forestall the inevitable questions about which country would be next. To the question of whether “consolidation is now the strategy of the day”, he said: “The answer is no.”

Despite that, the Grab deal has inevitably shone a spotlight on India, which has become the focus of one of the fiercest battles for market dominance. According to some bankers, this week’s move could set the stage for a similar departure, leaving the market to local rival Ola — itself backed by SoftBank, along with Chinese internet company Tencent.

SoftBank’s investment in Uber, which came alongside a fresh injection of capital into Ola, triggered speculation that it would push for a merger of the two companies. The pair control almost the entire Indian market but have been burning through cash in their battle for supremacy.

Kalagato, a local research company, estimated that Ola extended its lead over Uber in the second half of last year, based on app installation data, accounting for 56.2 percent of the Indian ride-hailing market in December against Uber’s 39.6 percent.

“The biggest beneficiary of these events is SoftBank, which … will see less of its investment dollars burnt on the bonfire of cut-throat competition the more it can reduce competition,” said Richard Windsor, analyst at Radio Free Mobile.

Mr Khosrowshahi has been keen to calm speculation about Uber’s position in India, declaring it “a key component of our growth plan” as well as “one of our healthiest markets in terms of growth rate” on a recent visit. But with consolidation now the order of the day, and SoftBank pulling the strings, the questions about Uber’s future will not be so easy to quell.

Please use the sharing tools found via the email icon at the top of articles. Copying articles to share with others is a breach of FT.com T&Cs and Copyright Policy. Email licensing@ft.com to buy additional rights. Subscribers may share up to 10 or 20 articles per month using the gift article service. More information can be found here.

https://www.ft.com/content/7b415e82-3098-11e8-b5bf-23cb17fd1498

Uber seeks new roads to open markets

Uber has not always had an easy ride. In Argentina, the car-hailing service was declared illegal and payment companies blocked transactions. Its experience in Germany wasn’t much better: its first, aggressive move into western Europe led to strong resistance from regulators.

New chief executive Dara Khosrowshahi is now on a charm offensive to try to reopen doors that have been slammed in Uber’s face. On a recent visit to Japan — a country, like Germany, where Uber has only a restricted and expensive black car service — Mr. Khosrowshahi pitched a new idea: that a company that had been known for its take-no-prisoners tactics could become a trusted partner of the local taxi industry.

In this new guise, the Uber app could act as the ordering mechanism for existing taxi services, or it could be the front-end for a fuller online marketplace with the same kind of dynamic pricing used to match supply and demand in Uber’s main markets.

That Uber is willing to consider new ways of doing business like this speaks volumes. After the legal and cultural clashes that made the company’s brand toxic with regulators in countries such as Argentina and Germany, a drastic rethink is needed.

- Financial Times

.